How broadband works

Broadband provides high speed data carried over a normal phone line without affecting the telephone service.

Terminology

The term broadband simply means a broad band of frequencies has been used. It is a radio term and normally means that multiple frequency carriers are used to carry one signal. It describes the way ADSL (Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line) services work so has become a term to describe a fast internet connection. The term is then being rather confusingly used to describe fibre connections which are not broadband at all, but use a single frequency laser.

- Also see: Exchange-to-premises-wiring, which shows the phone line equipment between your premises and the exchange.

Frequency

Normal telephone service is an analogue of sound waves. It carries sound using electrical signals that work in the same way as they do though air. In terms of frequency this means that telephone calls use very low frequency signals on the telephone line. This is called baseband.

The line itself can carry signals at a much higher frequency. The limiting factor is the quality and length of the cable used. Normal telephone lines are a copper pair (two insulated copper conductors twisted around each other) that can go for several miles from the local telephone exchange to your premises.

ADSL makes use of the rest of the capabilities of the cable. It carries data using a wide range of frequencies much higher than that used for telephone calls. The fact that it uses this broad band of frequencies is why it is called broadband.

Adapting to the line characteristics

One of the key features of ADSL is that it can adapt to work on a variety of line quality and lengths. A long line cannot carry the same range of signals as a short line. Lines can also suffer from specific interference which only affects some frequency bands. So the line will sync to start with.

Syncing means that each end sends a range of different signals and the other end reports back what it can hear. This allows the modems at both ends to work out what the line can handle, and what frequencies work. For each of hundreds of different frequency bands the modems agree how many bits of data can be carried at a time in that band.

What this means is that the line can work at different speeds depending on the length and quality of the line. If, over time, the line characteristics change the line will have to re-sync which usually means a short outage in service.

Margins

Re-syncs are a pain as they normally mean a broadband service stops for several seconds to re-establish the line characteristics. This is not generally a good thing. To help avoid re-syncs the initial measurements of the line characteristics are adjusted to allow a margin. This means not all of the line's capabilities are used. If the line degrades over time, and that degradation is within this margin, then no re-sync is needed.

Some lines are very stable, having the same characteristics all of the time. These lines need very low margins. However some lines vary a lot, and this can be over a daily cycle depending on temperature or weather conditions which affect the performance of the line and levels of interference affecting the line. Such lines need higher margins.

With BT ADSL and FTTC circuits there is an automatic system to establish that a line is re-syncing a lot and adjust the margin to be higher in future. This is called Dynamic Line Management (DLM) and runs all of the time. It can take a few days for a new line to get the right margins for stable operation when first install, but in practice it is rarely more than the first few hours.

The margin on TalkTalk lines can be adjusted manually by staff and customers.

Interleaving

The margin on the line sync helps accommodate general changes in the performance of a line over time. However, there can be interference that is more like "pops and clicks". Impulse interference that causes corruption of data. This causes packets to be lost and resent and so has the effect of making the overall performance of the line slower.

To accommodate this type of interference a system of error correction is used. This means extra parity data is sent, and if data is corrupted then this can be identified and corrected. It uses a small amount of the available bandwidth to provide this extra parity data but makes the line much less prone to errors. At the same time the data is interleaved. This means overlapping each block of data with the next and is the same trick used on CDs to make them resist the effects of scratches on the surface. The effect is higher latency (the time taken for data to get through the ADSL).

ADSL1

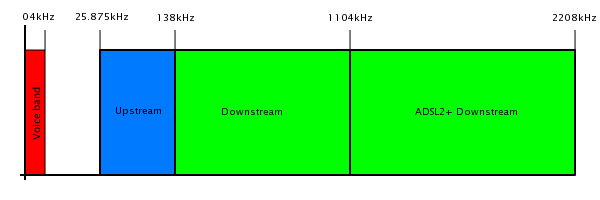

In the early 2000s, ADSL has been defined for use alongside normal phone service as well as alongside ISDN. The different frequency for ISDN means it is a different standard. In the UK we use ADSL over POTS (Plain Ordinary Telephone Service) following ITU G.922.1 Annex A which allows in theory up to 12Mbit/s downstream and 1.3Mbit/s upstream. However BT offer only 8.128Mbit/s downstream and 832kbit/s upstream maximum using ADSL1.

ADSL2+

In the late 2000s, A new standard for ADSL called ADSL2+ provided extended bandwidth. This follows ITU G.992.5 and provides up to 24Mbit/s downstream and 1Mbit/s upstream.

A variation of the ADSL2+ specification called Annex M allows up to 24Mbit/s downstream and up to 3.5Mbit/s upstream. In the UK we cannot achieve the full 3.5Mbit/s upstream as there is a frequency plan that must be followed on all phone lines to avoid interference. Therefore, in the UK, Annex M allows around 2Mbit/s uplink.

It is important to realise that the above is a technical statement about the ADSL2+ technology. An actual service will achieve a sync speed (which includes various overheads) depending on the line length and quality and other factors, and may even change over time. To assess the likely speed of your service, please use the availability checker.

VDSL

In the 2010s, Openreach started to offer VDSL Fibre To The Cabinet (FTTC) operates using VDSL from a street cabinet rather than ADSL all the way from the exchange. VDSL uses different frequencies and powers to ADSL but is otherwise very similar technology. VDSL can provide speeds over 100Mbit/s on very short lines. The speed available drops off quickly with distance - but this is not usually an issue as cabinets are usually close to premises. There are cases where FTTC can be slower than ADSL all of the way from the exchange.

It is important to realise that the above is a technical statement about the VDSL technology. An actual service will achieve a sync speed (which includes various overheads) depending on the line length and quality and other factors, and may even change over time. Services are available with speed caps set at 40Mbit/s or 80Mbit/s download, so higher speeds are not available even if the line can support it. To assess the likely speed of your service, please use the availability checker.

Fibre

In the 2020s, Openreach and many Altnets are deploying fibre optic cable (glass) can be used to provide a service to a customer premises, generally using PON (Passive Optical Network) technology, Fibre is usually a single frequency using a laser, so not actually broadband at all. Various services are available, see each service description for the speeds that are offered, typically between 80Mbit/s and 1000Mbit/s.

The Openreach FTTP rollout is progressing, with 25 million premises (80%+ of the UK) expected by December 2026

James Harrison provided an excellent talk PON/FTTP at EMF 2024

Some companies have previously branded coax based services as Fibre, which can muddy the water a little.

Beyond the exchange

The ADSL/broadband bit connects between your premises and the local telephone exchange, at which point the line is split between voice (for telephone calls) and ADSL. The local exchange is connected via fibre to one of 20 main interconnect points where a large fibre back-haul network connects back via gigabit fibre links to our rack in a data centre in Docklands. We are then connected by fibre so that we can communicate directly with hundreds of UK based ISPs as well as international (transit) links to the rest of the world.